Blue Marble Evaluation Context

The first overarching Blue Marble Evaluation principle is the Global Thinking Principle: Apply whole-Earth big-picture thinking to all aspects of systems change. The World Food Programme (WFP) epitomizes that principle. The pandemic, as a global challenge, requires Global Thinking. In evaluating WFP’s response to the pandemic, global thinking is critical.

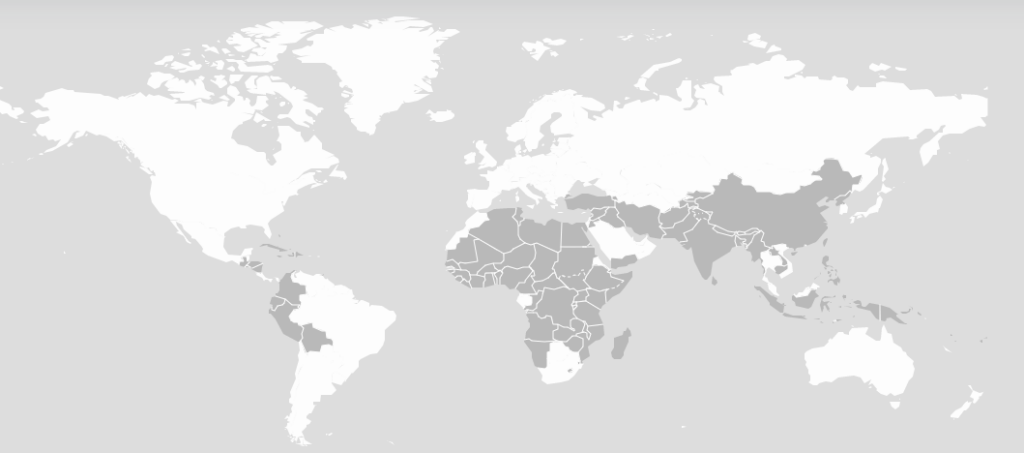

Working in 88 countries, WFP also manifests the GLOCAL Principle: Integrate complex interconnections across levels. The global-local interface means that evaluation must examine what is happening at headquarters, what is happening at the country level, and the interactions globally to locally and locally to globally.

The World Savvy Principle calls for and guides ongoing learning. This blog highlights the ongoing learning of WFP as it undertakes an evaluation of the organization’s response to the pandemic.

On March 23, 2020 I wrote a blog on “Evaluation Implications of the Coronavirus Global Health Pandemic Emergency.” It began:

- Adapt evaluation plans and designs now. All evaluators must now become developmental evaluators, capable of adapting to complex dynamics systems, preparing for the unknown, for uncertainties, turbulence, lack of control, nonlinearities, and for emergence of the unexpected. This is the current context around the world in general and this is the world in which evaluation will exist for the foreseeable future.

- Be proactive. Don’t wait and don’t think this is going to pass quickly. Connect with those who have commissioned your evaluations, those stakeholders with whom you’re working to implement your evaluations, and those to whom you expect to be reporting and start making adjustments and contingency plans.

The real world in real time today

Organizations, programs, and evaluations at all levels have been forced to pivot in the face of the coronavirus pandemic. As those organizational and programmatic responses have occurred, it is easy for evaluation to get left behind. The strategic and immediate humanitarian mandate is to: Respond! Respond! Respond! Evaluation will follow at some later time, perhaps.

Now, as we approach the official one year anniversary of the beginning of the pandemic, I want to report on evaluation of the COVID-19 response by one global humanitarian organization at the center of the worldwide response to the pandemic: the World Food Programme (WFP). They are undertaking a developmental evaluation of WFP’s response to COVID-19 and already important lessons are being learned that are likely to be relevant to other organizations. I’ve had the opportunity to advise on the evaluation, read background documents, and participate in some early evaluation team meetings. The WFP evaluation manager and the external evaluation team leader have been especially reflective and forthcoming about how the evaluation is unfolding. As I listened to the inception discussions and the early data collection experiences, it struck me that what they were experiencing and learning would be of value to evaluators worldwide as well as organizations that can benefit from WFP’s evaluation approach, even at this early stage of its implementation.

Context

To appreciate the significance and stakes involved in this evaluation of WFP’s response to COVID-19, a bit of context is necessary. The UN’s WFP is a major actor in the international response to the pandemic. As the world’s largest humanitarian organization, it plays a lead role in the UN’s Global Humanitarian Response alongside responding to the needs of partners and beneficiaries in the 88 countries it serves. By the end of 2020, WFP had received US$8.5 billion of confirmed contributions for 2020 against a total requirement of US$13.73 billion, of which $271 million came from the Global Humanitarian Response Plan.

Globally, at the beginning of 2020, almost 168 million people required humanitarian assistance and protection, a 15 percent increase since the beginning of 2019. Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, violent conflict, climate change and other human-made and natural disasters were increasing the number, scale, and complexity of humanitarian crises. With global humanitarian financing of $40 billion required for 2020, including responses to COVID-19, the humanitarian funding gap is growing (see COVID-19: Potential impact on the world’s poorest people: A WFP analysis of the economic and food security implications of the pandemic). At the same time, expectations by donors and politicians for transparency, accountability, and value for money of humanitarian assistance have been increasingly demanding.

Due to the impact of the pandemic, for the first time in over 20 years, poverty levels are increasing. The World Bank estimates that, as a result of the pandemic, an additional 88-115 million people will slide into extreme poverty by 2021, with income inequality increasing at the same time. Already acutely food-insecure people in need of humanitarian assistance – estimated at 149 million by WFP in June 2020 – are most vulnerable to the pandemic’s consequences, due to their limited coping capacity for both the health and socioeconomic aspects of the pandemic as well as their enhanced exposure to human rights violations and other protection risks. An additional 121 million people are at risk of becoming acutely food-insecure before the end of the year as jobs are lost, remittance flows slow, and food systems are stressed or disrupted. The potential effects of the pandemic are likely to negatively impact on food security well into 2021 and beyond.

The Nobel Peace Prize 2020 was awarded to World Food Programme (WFP) “for its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict.”

Evaluating WFP’s response to COVID-19: 12 Emergent Insights and Lessons

Lesson 1. The time for evaluation is now, not when the pandemic is over. Past WFP reviews (lessons learned exercises) and evaluations of humanitarian responses have pointed to the loss of information and knowledge that is disseminated in the early stages of a crisis response, but not adequately captured and stored for future use. This includes qualitative data and tacit knowledge used to inform decision-making. This brings to mind a learning exercise some years ago at the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) headquartered in Ottawa in which the evaluation unit conducted a study of when, in a five-year program, the most important learning occurred. The results showed that, overwhelmingly, the greatest amount of significant learning occurred during the first nine months of a new 5-year initiative, well before the first formal midterm reporting on progress halfway through the program. The IDRC key informant interviews substantiated that a great deal of that early learning was never captured.

Lesson 2. Synthesis evaluation is crucial to make sense of and capture important lessons of diverse efforts and reviews. A number of internal learning and review exercises regarding the COVID-19 response are underway within the many units and programs of WFP. The external and independent COVID-19 evaluation presents an opportunity to bring forward, synthesize, spotlight, make explicit, and make available cross-cutting lessons and insights.

Lesson 3. Complex systems understandings and thinking are critical. An evaluation of responses in a turbulent, uncertain, rapidly changing, and increasingly dangerous worldwide crisis requires a complex dynamic systems perspective to frame the evaluation. Knowledge gaps are emerging as WFP is called upon to deliver against more and more complex responses across the range of COVID-19 affected contexts. This evaluation, therefore, provides an opportunity to bring together learning across the corporate environment, from both programmatic and systems perspectives, and from the global to the country level, to identify major strategic achievements, challenges, and concerns.

Lesson 4. Evaluating adaptive capacity is a central focus. A framing question is: How have WFP capacities, systems, structures and procedures been able to adapt and respond to the demands posed by the COVID-19 pandemic? Adaptation has become the clarion call of response to the pandemic. Adaptive management. Strategic adaptation. Organization and programmatic adaptation. Budgetary and financial adaptation. Workforce and personnel adaptations. Work and life adaptations. Because the return to some kind of pre-COVID “normal” appears highly unlikely, and with the climate emergency looming large over the pandemic and well into the future, understanding, building, and evaluating adaptive capacity will be a core challenge for the foreseeable future.

Lesson 5. Developmental evaluation is well-matched to the evaluation challenges. In languages where the term “developmental” proves difficult to translate, I substitute Adaptive Evaluation. Approaches to evaluation have proliferated in the last 20 years. The key is selecting the approach that fits the evaluation situation and circumstances. The evaluation design has adopted elements of a developmental evaluation paradigm for the following reasons: (a) The distinguishing characteristic of developmental evaluation is ‘contributing to something that is being developed’. WFP’s COVID-19 has required major corporate adaptations which are not likely to come to a close in the near future; the scoping phase for this evaluation found consensus among informants that changes implemented may lead to longstanding shifts in how WFP both continues to respond to the medium and longer term impacts of the crisis but also to its wider business model. The presumption within developmental evaluation of a high degree of flexibility and adaptation, and a focus on emergence, is therefore appropriate. (b) The COVID-19 response in WFP functions in a systemic manner, taking place across corporate structures, systems and operations. As discussed in point 3 above, this makes systems thinking and complexity theory – both central to the developmental evaluation paradigm – highly relevant, particularly as WFP corporately undergoes transformation. As I noted in my March 2020 blog on the evaluation implications of the coronavirus pandemic, we are all developmental evaluators now. But developmental evaluation has had a hard time breaking through in large bureaucratic organizations that tend to have rigid, standardized, mandated, and top-down evaluation protocols and processes. WFP is therefore on the leading edge of experimenting with adapting developmental evaluation to evaluate adaptive programmatic and strategic responses to COVID-19. In the previous point, I suggested that the future will demand more attention to adaptive capacity and what is learned from WFP’s developmental evaluation experience will inform how to embed developmental evaluation into large, complex global organizations.

Lesson 6. Focus on evaluation use undergirds developmental evaluation (DE). DE is situated within the wider context of utilization-focused evaluation. Evaluating WFP’s responses to COVID-19 began with a focus on what the organization needed rather than being guided by standard evaluation formats in WFP or, indeed, a predilection toward any particular type of evaluation. Ongoing learning for management was voiced in consultations as a critical WFP organizational need going forward. Developmental evaluation emerged as the approach that best fit the situation and needs of the organization. One important consideration was that a developmental evaluation which is explicitly geared to providing useful evaluative input to support corporate learning, as WFP’s COVID-19 response evolves, can add value at multiple levels across the organization. Both the WFP’s independent Office of Evaluation and the external evaluation team are well-versed in what the evaluation use literature generally and utilization-focused evaluation particularly have learned about making evaluations useful. This includes (a) a high level of engagement with management and staff (HQ, Regional Bureaus, and Country Offices as appropriate), throughout data collection, and ensuring regular feedback loops to promote ongoing learning; (b) adopting an approach of openness, receptiveness and flexibility, and willingness to adapt the evaluation process where needed; (c). building a high level of ownership and decision-making, with findings, conclusions and implications for next steps presented by the evaluation team and collectively discussed in feedback events with learning groups throughout the evaluation; (d) a collegiate approach between the evaluation team, involving regular discussions and open communications, to harness collective expertise and experience of both evaluation commissioners and the evaluation team; and (e) attention to process management collaboratively between the WFP’s Office of Evaluation and the external evaluation team.

Lesson 7. A collaborative design process established collaborative norms for working together throughout the developmental evaluation. The process of designing the evaluation was highly interactive and collaborative, bringing together stakeholders across WFP, the independent Office of Evaluation, and the external evaluation team leader. The collaboration deepened as the nature and design of the developmental evaluation evolved through several items – Concept Note, Approach Paper, Terms of Reference – all of which made steps forward in thinking about, understanding, and clarifying developmental evaluation and its relevance for the task at hand. Once established in the design phase, the trust and mutual respect carried forward to undergird the implementation of the developmental evaluation on a collaborative manner.

Lesson 8. Evaluation leadership is essential for evaluation innovation and adaptation. A substantial literature exists about the importance of effective, visionary, and risk-taking leadership for organizational success over time. In contrast, directors of evaluation offices are typically thought of as managers rather than leaders, at least that’s been my experience. Yes, evaluation offices and evaluations have to be well-managed. But leading-edge evaluation approaches, like developmental evaluation, require visionary and committed evaluation leadership. That leadership begins with the decision to adapt and innovate in trying out developmental evaluation. Then, ongoing leadership is needed to explain, advocate for, and work through barriers that can emerge in the face of resistance and skepticism. As former American Evaluation Association president Kathryn Newcomer says in her forward in Changing Bureaucracies: Adapting to Uncertainty, and How Evaluation Can Help:

We all recognize that cultures are shaped by leadership. Leaders who embrace and reward learning, and walk the talk through visible allocation of their time and attention, and of their agencies’ resources are needed to empower leaders throughout their organizations to learn. Leadership – both political and career – presents the essential ingredient needed to enable evaluation to support and improve the work of public bureaucracies.

Evaluation leadership requires more than methodological knowledge and management excellence; it also requires astute political judgment to navigate organizational mazes; a commitment to and knowledge about how to build on existing evidence to further organizational buy-in and learning; interpersonal skills to establish and nurture the relationships critical to utilization-focused developmental evaluation; and the courage to stay the course when doubts and challenges arise as they inevitably do. For all these reasons and more, a critical factor in the success of developmental evaluation is leadership. Evaluation leadership is essential to finding the appropriate balance between diverse evaluation needs and approaches in an organization, including, especially, what often emerges as a seeming tension between learning and accountability.

Lesson 9. Balance learning and accountability purposes. Evaluators regularly confront tensions between learning and accountability. Accountability mandates and criteria can produce aversion to risk taking and give rise to fear of failure. Learning requires openness, trust, and honest interactions. It therefore becomes important when both learning and accountability are to be served by an evaluation to distinguish what is required to support each. To support learning consistent with developmental evaluation, consultative groups within WFP will be created to engage findings and promote cross-institutional learning. Consultative groups will comprise a cross-section of technical staff and management from headquarters, regional, and country offices, to ensure that findings and the dialogue emerging from them permeate across WFP.

To address accountability, the evaluation will give attention to assessing adherence to humanitarian principles, protection issues and access, accountability for affected populations in relation to WFP’s activities, as appropriate, and on the differential effects of the response on men, women, girls, boys with and without disabilities, and other relevant socio-economic groups. Among the most significant aspects, the evaluation will focus on assessing if and how programmatic adjustments contributed to beneficiaries’ safety, dignity and integrity. Accountability will include whether WFP adequately managed to overcome/mitigate humanitarian access issues that have been either introduced or exacerbated by the pandemic to reach beneficiaries. The tone and tenor of developmental evaluation is to support accountability for learning while learning how to address accountability concerns in ways that produce useful findings rather than just compliance (or noncompliance) judgments.

Lesson 10. Be prepared to address anxiety, resistance, skepticism, and “evaluation fatigue.” Developmental evaluation, like all evaluation, can produce anxiety, resistance, and skepticism. Given the pandemic crisis and accompanying stresses, it is to be expected that some, perhaps many, would be dubious about adding evaluation inquiries onto already overburdened staff. WFP engages in a lot of ongoing evaluation and to initiate yet another evaluation evoked concerns about being tired of evaluation: “evaluation fatigue.” Access to documents and staff can be resisted, delayed, and even denied. WFP’s Office of Evaluation and external evaluation team leader worked together to overcome barriers and communicate the rationale for and potential benefits of conducting the evaluation in the midst of the pandemic response. Getting buy-in is important. Top-down mandates to comply with the evaluation can undermine evaluation credibility and utility. Taking the time to negotiate cooperation and access pays off in better data and greater utilization.

Lesson 11. Frontline staff proved open to sharing and reflecting on their experiences. Once access to the field was gained, the evaluators found frontline staff eager to have their stories heard. Interviews in the first phase evaluation that were scheduled for 45 minutes would often last more than an hour, even an hour-and-a-half. Of course, this requires skilled interviewing and an adaptive approach to interviewing that follows the lead of interviewees about what’s on their mind and what they want to share. Developmental evaluation requires developmental, adaptive, flexible, agile, and emergent interview protocols and interviewers.

Lesson 12. Interviews in the midst of stress can be therapeutic, but great sensitivity and empathy are needed to avoid potentially deepening stress and trauma. Many frontline staff work under highly stressful conditions in conflict-laden contexts. Travel bans, quarantines, mandated sheltering in place, and restricted social interactions have meant for many long separations from families, friends, and support networks. These are stressful jobs to begin with, so adding pandemic restrictions only deepened the stress. The evaluation interviewers have had to build their capacity to conduct trauma-informed interviews in ways that can release stress and offer some comfort for interviewees in being heard and understood, and have their stories valued. The human story behind COVID-19 in the lives and work of frontline staff has come through as really important.

Looking ahead

These are early, still emergent lessons. But that is the nature of learning in complex dynamic systems where real-time understandings and insights can make an immediate difference. Just as now is the time to engage in developmental evaluation of responses to the pandemic, now is also the time to be reflecting on and learning from those evaluations.

Note: In writing this blog I drew heavily upon the evaluation’s design proposal. I’m especially appreciative of the insights of Deborah McWhinney, WFP’s Office of Evaluation lead for the COVID-19 response evaluation and Julia Betts, external evaluation team lead. I could not have written this blog without their collaboration, but the opinions expressed herein are my own as are any errors in what I’ve reported.

Principle 1: Global Thinking, Principle 6: GLOCAL, Principle 11: World Savvy